In 1965, we embarked on a modest plan to attempt rehabilitation of injured owls to the point of responsible release. We soon realized that while many of the souls brought into our care were unreleasable, they were not completely lost. Most owls admitted to The Owl Foundation are hurt due to human interference, not because of poor genes. Most are hit by motor vehicles, however some hit windows during migration, or are orphaned when trees are cut down or parents killed - often by cars.

As such, The Owl Foundation quickly took on a challenge: to recycle healthy genes back into wild populations by breeding permanently damaged wild owls and releasing their progeny back into the wild where the parents originated.

We soon learned that to do this successfully we would have to provide the opportunity for damaged birds to make their own choices in every aspect of their lives.

These choices include:

- the ability to move from one defined space to another through overhead corridors

- to meet others of their species

- to choose a territory

- to select every size and type of roost, of all heights, of exposure or seclusion

- to select from two to four available nest sites in each territory

- to be alone or in company

A Snowy Owl (Nyctea scandiaca) feeds her chicks amongst the

safety of naturally growing ground cover. Her scrape is not even visible

from outside the cage.

As the young age, they will leave the nest site and hide in the vegetation as they would in northern Canada. Their father keeps a watchful eye on them and brings them food while mom caters to the chicks still in the nest.

All of this involved withdrawal from public visitation, since these are inherently wild but traumatized owls and spaces for recovery must be very large. This need is not just to promote the likelihood of ultimate breeding, but also to provide a suitable habitat for young owls' early experiences.

To further complicate matters, each owl species has its own specific needs. After much trial and error, we have evolved typical breeding facilities for each, designed with these needs in mind (Long-eared owls (Asio otus), for instance, are timid and caging is designed to offer a myriad of areas hidden from view). To date, The Owl Foundation has successfully bred all but two of Canada's owl species.

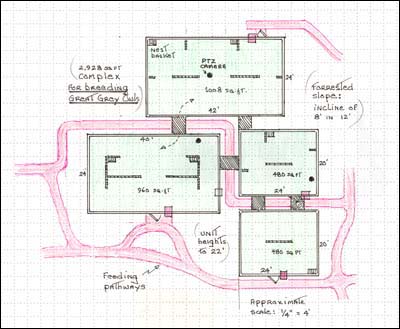

The common design to all breeding owl cages is relatively simple:

Each complex is made up of three large, double compounds, linked to each other by flight corridors.

Into the complex we put six owls of one species, both sexes, and all corridors open. We seldom know whether the occupants have had previous pair-bonding experience in the wild, a factor that may delay new bond formation as the now captive partner apparently waits for that bond to dissipate before beginning negotiations with a new individual.

With luck, a pair will form and claim one of the compounds. Another unit may be selected soon after by a second pair. The last two birds, left unpaired, can then be transferred (often through corridors) into another complex of similar setup, with new potential mates.

The third, empty unit, is reserved for the progeny of the two pairs.

Northern Hawk Owl (Surnia ulula)

Breeding Complex.

Made up of seven individual territories

with interconnecting corridors for

pairing and dispersal.

By early autumn, any young produced begin to disperse from the parental territories into the free territory through corridors.

It is interesting to note that the parents rarely stray outside their own nesting territories during this time and, in fact, tend to promote the juvenile departure.

The corridors are then closed and live training in the juveniles' unit can begin with vigor. This corridor system is crucial to the continued health and breeding of both the adults and progeny. The young owls have undergone natural fall dispersal from their parents and have never been handled by humans. The adult breeding pair, having successfully raised a family with no interference, continue to consider their territory safe for future nesting.

Contact

Us | Hours | Home

| Legal

© 2010 The Owl Foundation